Steve McClaren sat on a bench in the away dressing room at the City Ground and watched Alex Ferguson debrief a Manchester United side who’d just earned the club’s biggest away win in almost a century.

It was McClaren’s second day as Ferguson’s assistant. Three days earlier, he was the No 2 at Derby when they headed north to face United. Derby travelled back defeated but only narrowly, beaten by a single Dwight Yorke goal. The team coach pulled back into the car park of their Pride Park stadium around 2am. As the squad disembarked, the manager, Jim Smith, pulled McClaren aside.

“Obviously you know what I’m pulling you about,” he said, aware that Ferguson had spoken to McClaren on the phone the previous weekend about replacing Brian Kidd at Old Trafford. “Get in the car tomorrow, drive back up there and make sure you don’t come back.”

When, in his office at the Cliff, Ferguson had told Albert Morgan to prepare some kit for McClaren, who’d be meeting them at their hotel in Nottingham the following day, the kit man replied: “Who the fuck is he?” The players were similarly surprised by the identity of the new No 2 when they first met him on the eve of the Forest game.

They knew Kidd. They liked Kidd. They didn’t know who the new guy was.

Ferguson instructed McClaren to observe Saturday’s proceedings at the City Ground. His input wasn’t yet required. That could wait for Monday, when he’d oversee his first training session. So McClaren watched as the goals flew in, as Yorke and Andy Cole split four between them. He watched as Ole Gunnar Solskjær plundered another four all for himself. And he watched as Ferguson delivered the kind of post-match team-talk that suggested 8–1 victories are nothing out of the ordinary for this club.

Andrew Cole celebrates after scoring Manchester United’s third goal in an 8-1 win at Nottingham Forest. Photograph: Action Images

Although, geographically, he was only 13 miles from the venue in which he’d burnished his coaching reputation over the past four years, McClaren couldn’t help but feel he was suddenly a long way from Derby.

“Oh my God, what the hell do I do?” he thought to himself. “How do I coach this team?”

He turned to Morgan, who was sitting beside him. “Is it always like this?” he asked.

After Kidd’s departure for Blackburn, Ferguson whittled down his list of potential replacements to two names: David Moyes, the No 2 at Preston, and McClaren. It was around mid-January that McClaren discovered he was under consideration for the English game’s top assistant’s role.

“I was at a dinner,” he says. “I think it was a journalists’ dinner. Someone I know pretty well, a journalist, mentioned that my name was in the frame for the job at United that Brian had just left. I said: ‘Don’t be silly.’ He said: ‘No, no, you’ll see. You’ll get a call in a couple of weeks.’ I never thought anything of it. Then, two weeks later, I did get a call. It was from the gaffer. It was the Saturday night before we played them the following midweek. He said: ‘Are you interested in coming to United as assistant?’ I said: ‘Of course I am.’ He said: ‘OK, we play you Tuesday. I’ll have a word with Jim straight after the game and see if he will allow it and I’ll get back to you after that.’ I kept that quiet and prepared for the game as normal.”

When planning for his first session at the Cliff, McClaren encountered a quandary that had never arisen with Derby – how do you improve a team who have just won 8–1?

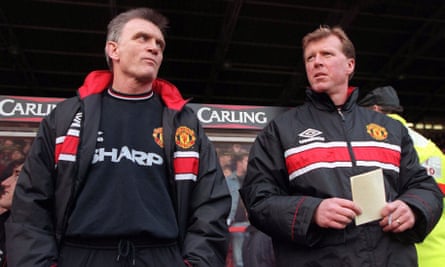

Steve McClaren (right) with Jim Ryan on the touchline at Nottingham Forest. Photograph: Action Images

“It was kind of a baptism of fire,” he says. “But I focused on the one goal Forest had scored and thought: ‘Right, I’ll focus on that, because they can score goals.’ Just leaking one goal, I thought at least I could call that a weakness. It’s something that the gaffer wanted anyway, clean sheets. That gave me the perfect way in. But, saying that, Monday morning was still very, very daunting, coaching these world-class players and this world-class team.

“It was a massive, unbelievable difference from Derby. The players were very focused, very competitive. One of the main things at United was about the intensity that the gaffer wanted in training. You’ve got to work hard in training. The level of work, the intensity of work and the competitiveness was top. Talk about high-performance culture – this was the highest at that time. I’m grateful I had three years of experiencing that. It certainly stood me in good stead, seeing the standards of a high, top-five-per-cent-performing team. This was the standard that’s required if you want to be top, top. It’s always been a benchmark everywhere else I’ve been. I’ve never attained the heights of the environment, the culture, the competitiveness of what Manchester United had in those three years. It was just driven every day by the players. I just had to feed their desire, their hunger, their drive, their competitiveness and give them sessions that fed that while also controlling it at the time.”

The players quickly responded. Like with Kidd, they found his affable nature a welcome antidote to Ferguson’s intensity, while McClaren’s methods provided some much-needed modernisation within the dated confines of the Cliff.

“He put on great sessions,” said Gary Neville, “some of the best I’ve been involved in – sharp, intense, full of purpose, but also fun.” The players soon appreciated how McClaren’s work on the training pitch translated to key improvements on matchdays, too. There was a feeling that the new coach and his methods could help them overcome their greatest hurdle.

“He changed the way we defended and we were more prepared when we played in Europe, with how we defended and how we played together,” says Henning Berg. “The back four became more organised. The distances between players was better and the cooperation with the midfield was better. Before that, we felt we had the best players and we could win every game going man for man. We would win most games in England, but in Europe we needed a little bit more. He had a big impact on our development as a team.”

As well as McClaren settled, there were stark reminders of how the expectation levels differed greatly from anything he’d experienced. After returning to the dressing room following a 1–0 win early in his time with United, McClaren applauded the players. “Well done, boys,” he said. “That was a great win.”

Roy Keane stood up.

“Steve,” the captain said, “It was a win, but we were shit. One thing we need around here is honesty. If we played crap, tell us we played crap.”

When it came to the delicate art of post-game praise, Ferguson imparted some sage advice. McClaren says: “The gaffer, said to me: ‘When they win, they only need two words: well done. No more, no less. Just ‘well done’ and we move on’.

“It was quite an abrupt kind of culture. An honest culture. Don’t over-praise. Don’t get too down. If we win, well done. If we lose, tell us how we need to win again and don’t give us any rubbish.”

This is an edited extract fromThey Always Score: The Unforgettable, Improbable, Iconic Story of Manchester United’s Treble Winners (Polaris Publishing, £20) by Ryan Baldi