‘He was a natural snooker player’

As a 16-year-old trainee press photographer for the Stockport Advertiser, I was sent to Marple Golf Club to photograph a charity golf day cheque presentation. It was May 1976 and Manchester United had just lost to Southampton in the FA Cup final. When I arrived, I was told there was a delay. Two minutes later Bobby Charlton arrived to receive the cheque on behalf of a cancer charity.

We were both waiting and, seeing a snooker room, Bobby said: “Do you fancy a game?” Twenty minutes later, the club captain interrupted and said they “were ready, Mr Charlton”. Bobby replied: “We’ll be there in a couple of minutes. Andy and I are just finishing this frame.” A red-faced captain left us. I couldn’t play snooker, but Bobby Charlton was a natural, explaining his shots as he potted them and giving advice on the one or two shots I had. At the end, he shook hands and said well played. I took the classic local newspaper presentation picture and left.

Walking up the drive to the main road, to catch my bus, a Jaguar drove past me then stopped a few yards ahead and waited. It was Bobby Charlton. He gave me a lift home while chatting about football and the FA Cup final, and asking about my work and family. As a 16-year-old I remember being a bit overawed and excited. As the years have gone on I’ve realised just how gracious and humble he was. He took care to treat me with respect and I was very grateful for his kindness. I came to realise just how important it is to treat everyone equally – a lesson Sir Bobby Charlton embodied every day. Andy Manning

‘He also had a sense of humour’

I grew up in Manchester and got a season ticket to Old Trafford when I was eight. As a bit of a contrarian, I also had a Scotland shirt (because that seemed to annoy my friends who supported England). When I was about 10, my mum and I ran into Bobby Charlton. As I was too shy, my mum approached and asked: “Can my son have your autograph?” With a quick glance at my Scotland shirt, he responded: “Not wearing that shirt.” He then winked, flashed a grin and politely signed. I can’t add anything to the tributes about his legendary play but, given all the words about his austere manner, I just wanted to add that he also had a sense of humour. Mark Childs

‘He was not a celebrity. He was bigger than that’

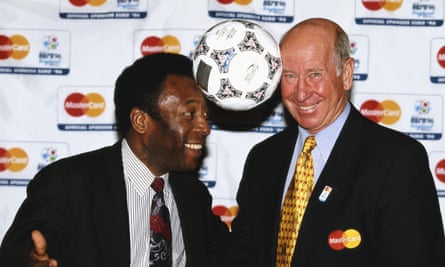

I had lunch with the Manchester United team, including Andy Cole, Gary Neville and The Voice of Old Trafford, Alan Keegan. It was fantastic with great conversation - we talked as much about their personal lives and families as we did about football and the club. The highlight, though, was meeting Sir Bobby, who was affable and kind. He is a true legend. He was neither a celebrity nor a superstar – he was bigger than that. His grace and humility made him unique. From a sporting perspective, he belongs in such vaulted company as Pelé and Muhammad Ali. It’s a short list. John Lynch

Pelé and Bobby Charlton in the mid-1990s. Photograph: Getty Images

‘Bobby floated all over the pitch’

I was born and raised in Altrincham, now Greater Manchester. I would play for the school team on a Saturday morning, grab some chips and head off to Old Trafford one week and Maine Road the next. These were days before football turned tribal. As a lifelong Blue, I was privileged to watch Charlton, Best and Law one week and Lee, Bell and Summerbee the next.

I remember watching Bobby floating all over the pitch. He was such a natural athlete, never the fastest but always one step ahead of the rest. He was a brilliant reader of the game. And what a shot; left foot or right foot, it didn’t matter. He never saw eye to eye with George Best – a slight difference in lifestyle – but they had a brilliant understanding on the pitch. I will be 70 in February. Football has always been a huge part of my life and Bobby is up there with the greatest players I have ever seen. RIP and thank you from a lifelong Blue. Howard Parkinson

‘He smashed a thunderbolt shot into the top corner’

The first time that I met Sir Bobby was on 22nd October 2005, just after I had joined Manchester United as a scout. My family and I were fortunate to have been invited to the directors’ lounge after the match against Tottenham. We were introduced to Sir Bobby and he joined our table. I remember him to be a quiet, dignified man with a real presence. The aura he exuded had more to do with the way others behaved around him than anything that he said or did himself. We were in the company of football royalty. He was so gracious when he invited us to see the trophy room with him and he had no hesitation in agreeing to a photograph with us. That day was when I first realised I had just joined a great football club.

I remember attending a coaching event in 2009 in Israel for 150 children from Arab and Jewish communities. He was dressed in an immaculate cream linen suit and stayed for over an hour in 30C heat giving out signed shirts, talking to kids and meeting the coaches. One of the coaches was running a shooting drill and I vividly remember Sir Bobby asking for a ball to be passed to him and then, to our amazement, he smashed a thunderbolt shot into the top corner of the goal from 25 yards out. Everyone was transfixed by what they had witnessed. It was made even more impressive by the fact that he was 72 years of age and wearing a suit and a pair of brown slip on loafers.

One of the joys of being a scout is meeting former professional footballers who work in the game and listening to anecdotes about their career. Pat Holland is one such character. He played nearly 250 games for West Ham and won the FA Cup in 1975. Pat told me that when he was making a name for himself in the first team he was selected against United. He was a very good prospect and touted to be a future England player. He described a moment that brought him back down to earth. Bobby Charlton had the ball in his own half and Pat decided to advance towards him and put him under pressure. As Pat went to close his space down, Bobby glided past him imperiously with a burst of acceleration and, without breaking stride, played a 40-yard diagonal forward pass straight to a teammate. He ran on to receive a return pass before crashing a shot into the net from 30 yards past a stunned, motionless goalkeeper. Pat knew at that moment that he would never, ever be that good. John Lambert

‘While washing his car I saw all of his England caps’

In the early to mid-1970s as a paper boy I delivered newspapers to his house in Lymm, Cheshire. As a cub, I also washed his car. As I washed it I looked through the front window of his house and saw all of his England caps. It was truly incredible. Simon Horn

Charlton wearing his 100th England cap at home in Lymm. Photograph: PA

‘I have never seen a ball hit so hard’

In 1962 I started going to Old Trafford regularly with my schoolfriend. I barely missed a home game until I went to university in 1968. Unfortunately, I missed the European Cup final as I had an A-level exam that day – it was general studies and has been of no use to me ever since.

I saw many great performances but the best was the 1967 Charity Shield against Spurs. The game had everything: Pat Jennings scored by kicking the ball out of his hands the full length of the field and Bobby scored two absolute thunderbolts. I was behind the goal at the Stretford End for both and have never seen a ball hit so hard. The second was struck from over 20 yards and hit so fiercely that it went in over Jennings’ head before he could even react. In an age of real hard men Bobby never reacted or retaliated but was hugely competitive and committed. The only aspect of the game where he struggled was tackling, but we had Nobby Stiles for that.

In Best, Law and Charlton, United were blessed with three truly great players who were each totally different. Law and Best could occasionally suffer from the red mist but never Bobby. To watch him was to realise that football could be an art form. He and Matt Busby did as much as anyone to make United the most well known club in the world. Peter Richardson

‘Even in the most remote parts of the world they knew Bobby’

I went to Argentina in 1997 with the intention of making my way to a valley in the middle of the Andes where a plane had crashed in 1972. Two of the survivors had climbed a very high mountain and walked to the Chilean foothills to get rescue for the rest of the survivors. I really wanted to see that mountain so went to Mendoza. The tourist office said it would be impossible but a young Argentinian woman told me of a small village deep into the Andes called El Sosneado where she had met a gaucho called Jose Teletai who knew how to get to the crash site.

He said he would take me for $400 if I could ride a horse. José could not speak English and I spoke only a little Spanish. We were together for three nights wild camping in the Andes and conversation around the campfire was difficult. One night I asked if he knew any English words at all. He shook his head sadly. Five minutes later he suddenly smiled and said: “Ah sí, Bobby Charlton.” That says it all about Sir Bobby. I was in one of the most remote parts of the world with someone who had never been anywhere else, but he knew of him. Jules

‘I met him on one of my first journalistic assignments’

The first goal I can remember seeing on the box was Charlton’s majestic strike (and England’s first in the tournament) against Mexico at Wembley in the 1966 World Cup. I saw Charlton live (though I only have dim memories) first when he was part of the Manchester United team that beat my team, Preston North End, in the FA Cup 2-0 in 1972 at Deepdale and then when he was player-manager for the Lilywhites.

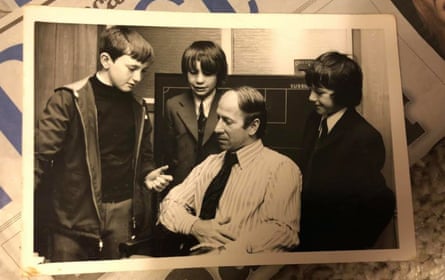

I met him on one of my first journalistic assignments (for the school magazine) when we wrote to the new North End manager requesting an interview, never imagining we would get one. Of course he gave us as much time as we wanted and as it was a scoop all three of us on the “editorial board” wanted to go along! That’s me on the right. Tony Paley

A young Tony Paley and his editorial board interview Bobby Charlton.

‘It was a small gesture but it had a big impact’

The school where I taught became affiliated with the Manchester United foundation in the mid-2010s. As head of art, I was asked to produce a series of paintings by my GCSE students of United players – not the ideal starting brief for me as I’ve been a Liverpool season ticket holder since 1989. However, it was arranged for Sir Bobby Charlton to visit the school, meet staff and pupils, and see the students’ United themed portraits. As a gift for Sir Bobby, I painted a portrait of him in his mid-60s pomp at Old Trafford.

Sir Bobby arrived with his wife Lady Norma and, after he chatted with some students, I presented him with the painting. He seemed genuinely appreciative and humbled. I had a talented but wayward student in the group who was a big United fan. I ushered Sir Bobby over to see his work (a portrait of him) and have a chat. Sir Bobby finished by signing the back of the student’s painting. That student was so full of pride and he really buckled down for the rest of the course. It was a small gesture by Sir Bobby but it had a big impact. Sir Bobby was very humble and he spent far longer than I expected with Lady Norma (who was also lovely) looking at the artwork, and chatting with everyone. I did wear my red Liverpool tie that day and Sir Bobby was very complimentary about Jürgen Klopp while we chatted. Mike Fox

‘My dad played against Bobby in a youth match’

Despite coming from Moss Side and a City-supporting family, my dad was a red because of Bobby Charlton. He played against Bobby in a youth match in which Bobby scored all his team’s 12 goals and my dad scored the one for his team. There was no childlike sulking, just sheer awe, even at that age. After the war when United shared Maine Road, my dad used to sneak into the ground every week to alternately watch both teams.

‘What they say about him being a gentleman is true’

I was a cub reporter on the Mexico 86 World Cup. My first assignment was to go to the draw. When it was over and I was leaving the building, I saw Bobby and ran after him. When I caught up with him, I was panting because of the altitude in Mexico City and, being a complete novice, had no idea what to ask him. He looked at me kindly, immediately assessed the situation and asked me: “Would you like to know what I thought about the draw?” What they say about him being a gentleman is absolutely true. Guy Hayward

Charlton at Highbury in 1959. Photograph: Evening Standard/Getty Images

‘We led him to a greasy spoon after a match’

I met him after a match in Blackpool. Along with two or three other boys, I walked with Bobby Charlton and Denis Violet from the players’ entrance to the town centre. Bobby wanted to know where he could get a cup of tea so we led him to a greasy spoon cafe near the stadium. The cafe was closed, so we kept walking, Bobby limping from an injury sustained that afternoon. He wanted directions to the station, presumably to make his way back to Manchester.

Things were very different in those days. This was 1960 and here was England’s best footballer, with an injured leg, finding his own way back to Manchester after a match at Blackpool. There was no team bus. Perhaps he even had to pay his own bus fare back to Manchester, out of his £10-a-week wage. Colin Talbot

‘He was 45 but we couldn’t get near him’

When I was 15 (41 years ago), I went to the Bobby Charlton Soccer School in Manchester for a week. He was always there and never in a hurry to be anywhere else. We were just kids who still thought we could play professionally given the chance. Bobby and his staff must have known we had no chance but that didn’t stop them from treating us all very seriously while nurturing a sheer love for the game, even if our future was in Sunday leagues, pub sides and supporting our clubs. Bobby joined in a lot of our training sessions and five-a-sides. I remember realising then what it was that set professionals apart from enthusiasts. He was 45 but we couldn’t get near him. He didn’t run – he floated. And he didn’t once showboat.

I recall his strong but never loud voice constantly encouraging us. His love for the game was clear and constant. In one of the sessions, a very young boy asked him what the Munich disaster had been like. I winced, and do now at the memory, but Bobby answered him calmly and explained that it had been horrible and he would never forget it. He was easy to love and respect even though he was a United legend and I am a Liverpool fan.

He talked about how many days on end he kicked a ball against a wall as a kid, perfecting his timing. Practice, practice, practice. And he said: “Always shoot - you never know, you might get a deflection and a goal.” Of course, that was coming from a man with one of the greatest gifts in shooting who ever lived, but he made it sound like anyone could and should have a go. That was his legacy. He loved the game and he had no ego to spoil anyone else’s chance of loving it, too. Andrew Fox

‘We were in awe’

In 1958, after the Munich disaster my uncle decided my school would raise money for a Manchester United memorial trophy. We were about 10 miles from Ashington, where Bobby Charlton was from. Money was raised and schools in the area played in a football competition. The final took place on the morning of the FA Cup final between Manchester United and Bolton. My school won. My memory is that I scored the winning goal but I may be wrong. A few weeks later we were presented the trophy by Bobby Charlton. We were 10 years old and in awe. I still have the “cup” we received – it’s about three inches high. More than 40 years later, I met Bobby and he said he remembered the occasion. I don’t care whether he did, it was so nice. All the team remember him so well. Roy Ritson

Bobby Charlton in hospital in 1958 after the Munich air disaster. Photograph: Zuma Press/Alamy

‘I saw him play as a 16-year-old for United’s reserves’

He was at his greatest the year after the Munich air disaster. That year Bobby took United to the FA Cup final. He scored impossible goals and won games for them when they had no hope. He single-handedly got them to the final.

I first saw him play when he was 16 and in the reserves at Old Trafford. The word was out that United had this young lad who was going to be very good. People went to reserves matches just to see Bobby Charlton. I met him before the 1966 World Cup when the England team were training at Lilleshall. The team had an open day before the games started and I took a busload of schoolboys down to see the players. We mingled with the players, and I met and chatted with Bobby. There was no security and everybody mixed freely. He was a player and a man you could be proud of. Bert Morris

‘He was warm, smiling and chatty’

In 2011, my students and I campaigned for blue plaques to be put up on the houses of the players who had been killed in the Munich air crash. Sir Bobby unveiled the Duncan Edwards plaque. He came into the school and spent a good few hours talking to the students. He was very different to how I expected him to be. On TV, he came across as unsmiling and a bit cold. However, with no cameras present, he was warm, smiling and chatty. I spent about an hour chatting with him and it was such an honour. He was a gentleman. Christopher Hirst

‘He must have signed a thousand programmes’

I met Bobby Charlton in Amsterdam at the old Ajax stadium in September 1976. It was United’s first game in European competition since they had lost the European Cup semi-final against Milan in 1969, after the club had been relegated and then promoted. I had been travelling around Europe with friends for a month and we spent our last evening watching United, followed by sleeping in a multi-storey car park. United lost a rather dull game 1-0. At half-time Bobby came into the away section of the ground – to be with the fans, to be supporting United and to be part of European football again. He must have signed a thousand programmes, including ours. Steve Kelly

Bobby and Jack Charlton. Photograph: PA Photos/PA Archive/Press Association Images

‘He gave me some great memories’

In August 1969 I had a summer job in Benllech Bay in Anglesey, where Sir Bobby had a house. United played Crystal Palace on the Saturday and, on the Sunday evening, a familiar figure came to the small kiosk where I worked to buy some cigarettes – most footballers smoked then. I was so nervous and uttered: “You’re Bobby Charlton and I’m a Manchester United fan.” He just smiled, paid the two bob and went on his way. It’s a moment I have never forgotten. I saw him play many times, home and away, and he gave me some great memories. Peter Gilbert Summers

‘He was a great darts player’

I was at school in Lymm in 1967, when Bob Charlton lived in the village. As teenagers my chums and I used to nurse the occasional half pint of mild while developing our darts skills in the back room of the Bull’s Head pub. It was a considerable surprise to us when one evening we were joined by Bob Charlton and Pat Crerand, who challenged us to a game. They were very cheerful and amicable – and both were entirely unassuming. They murdered us! He was a great darts player. Graham Williams

‘I remember the parade after they won the World Cup’

My mum went to school with him in Bedlington and lived beside him in Ashington. I never believed her until we met him in a shop in Newcastle, where he knew her straight away and they had a long chat. He was so humble. I remember Jack and Bobby being paraded around Ashington in an open-top car after they won the World Cup. David Burdis

Bobby and Jack after winning the World Cup. Photograph: Trinity Mirror/Mirrorpix/Alamy

‘I had to take a crate of beer into the dressing room’

I was an apprentice at West Brom. Manchester United were playing us at the Hawthorns. My hero was Denis Law and I was so transfixed when I met him that I didn’t really appreciate that Bobby Charlton and George Best were also in the dressing room. One of my chores was to ensure a crate of beer (I’m not lying) was in the dressing room for the players after the game. As I placed the crate underneath the treatment table, Sir Bobby said (and I paraphrase): “Right lads, let’s get on the road and grab a couple of pints.” I was taken aback. Bobby Charlton drinks! God, I was so naive. Gerry Adair